When Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace released in 1999, reception was mixed to put it lightly. While many children (including myself) enjoyed the movie, it sent ripples of anger through the more adult Star Wars fanbase and drew ire from movie critics overall. While many, many, many…many dissections of Phantom Menace have been completed since that 1999 launch – what’s one more?

For my own examination into the film, I want to focus primarily on Jar Jar Binks – a side character who drew particular ire for what many fans saw as his annoying nature or tendency to devolve the film into dirty humor (fart and poop jokes). Let me say this now – this is not intended to be a “hate” essay. I have nothing but respect for Ahmed Best, who has suffered more than enough at the hands of harassing jerks and jackasses claiming to be Star Wars fans.

This article is intended to view only how Jar Jar Binks was written. Let’s examine what kind of character Jar Jar was supposed to be and what function he may have been intended to serve in the story. For those who have seen the film and want a refresher, here is a rundown of every scene with Jar Jar Binks present:

What type of character was Jar Jar supposed to be?

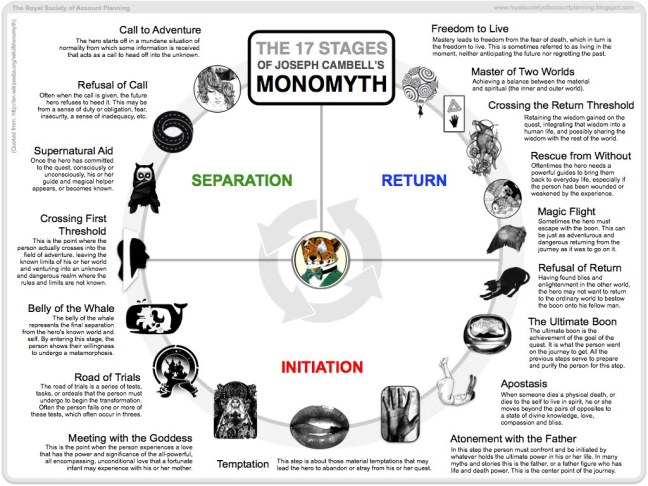

When George Lucas first conceived of Star Wars, he drew a great deal from the past. One of his primary inspirations was Joseph Campbell, a renowned mythologist who had spent years analyzing ancient myths from across the world. Campbell believed in the idea of the “monomyth” or that every heroic tale from the past has a common core and can be broken down into similar elements.

For instance, many heroes begin their journey as outsiders, drawn into a larger conflict rather than being present with it from the very beginning. Going on said hero journey challenges the protagonist, who ultimately returns victorious but a changed person. Lucas used this idea and many others from Campbell in his original Star Wars trilogy, and the themes have been present in the series ever since.

Using Campbell and this idea of monomyth means relying on established archetypes. An archetype is a typical example of certain person or thing, or an idea that has been replicated many times over. For instance, a bully is a character archetype. Every bully shares certain traits – namely intimidation and an abusive nature. The idea of a bully has become so ingrained in society that simply saying the word evokes a near complete image.

When Lucas created his characters for Star Wars, he used archetypes to form the foundation. Luke Skywalker – the heroic outsider, Obi Wan Kenobi – the wise old mentor, Han Solo – the scoundrel with a heart of gold, Princess Leia – the princess in distress: All of these characters came from an already established foundation of traits and personality. When Lucas wrote the prequels, he attempted the same thing. It is easy to read Shakespeare’s Othello in the tragedy of Anakin Skywalker or Oedipus in his desire to alter a prophecy.

Regardless of how well it worked, Lucas clearly had visions of grandeur on his mind. So, what about Jar Jar? Where does he fit in?

Jar Jar as the fool

A popular character archetype that owes a lot to Shakespeare is the fool or clown. This character is, by nature, ridiculous and outwardly very stupid. They are usually of low stature and aren’t doing well in their life. However, they are apart from the situation – no one directly trusts the fool, but the fool is typically present. This can give them wisdom, as they tend not to have subtly. When a fool speaks, they state the obvious, which can include information that the protagonist has overlooked.

A famous fool includes Dory from Finding Nemo. What she may lack in brains, she makes up for in wisdom, directly stating the flaws in Marlin’s parenting techniques.

Is Jar Jar a fool? He is certainly ridiculous enough to qualify on that level. Jar Jar is clumsy, clownish and prone to self-deprecation. However, what wisdom does he bring?

There two scenes that may qualify. The first comes at his introduction, right after he has met Obi Wan Kenobi and Qui Gon Jinn. Jar Jar suggests that they seek the gungan city for shelter and to hide from the droid army.

In the second scene, an anxious Padme is reflecting on the plight of her people. Jar Jar happens to mention that his race, the gungans, have a huge army that can challenge the invading droid forces. While Jar Jar never directly states that the gungans can help, Padme uses this information later to make her plan to fight back.

Jar Jar also states that relations between the naboo and gungans are strained but really doesn’t elaborate further. As far as this writer’s recollection, these are the only moments where Jar Jar may fit the mold of a fool.

Jar Jar as the heart

A more recent character archetype is the heart. Born out of many television ensembles, the heart is a member of the team that has no real special talent or skill. However, they serve as a moral compass, helping every other character around them maintain equilibrium and a healthy psyche. Hearts can be smart or stupid, strong or weak – but their primary strength must always lie in their emotional capacity.

The character Bolin from The Legend of Korra is a heart. While never stated, it is implied that he is not as strong a fighter as Korra or Mako, nor is he particularly smart. Instead, Bolin is trusting and giving, always there for friends that need a hand. His primary motivation comes from a desire to help others, a trait common in many heart characters.

The Heart can be similar to a fool, but with more positive intentions.

At first glance, Jar Jar Binks may look like a likely heart. However, there are problems with this fit. Jar Jar is often reluctant to help, oftentimes being volunteered for assignments he didn’t ask for. Also, apart from the Padme scene, Jar Jar is rarely shown comforting another character.

Jar Jar as the unlikely hero

At the heart of Star Wars is a love for the unlikely hero. Anakin, Luke and Rey have all come from humble origins to take center stage in galactic affairs. The same can be said of Han Solo, Finn, and Rose. None of these people began with the traditional, noble heritage of a hero – they instead earned their place through courageous acts or unnatural talent.

Jar Jar Binks definitely fits this bill, at least on the surface. He comes from nothing – an outcast of his own people. By the end of the film, however, he is a victorious general and well on his way to becoming a senator that will represent Naboo on the galactic stage. From a storyboard perspective, Jar Jar fits this archetype to the letter.

But let’s look closer: Is Jar Jar a hero? Does he in fact do anything to really save the day? Jar Jar’s role in the finale is to lead the gungan army against the droids. It is intended as a diversion to allow the other protagonists to act. Jar Jar loses this battle and is captured. Faced with this development, he promptly surrenders.

When Anakin destroys the droid control ship, the droids are deactivated and the gungans saved. Given how he acted, I say it is reasonable to compare Jar Jar more to a character in distress rather than an active hero. He is never looking beyond his personal safety.

Writing exercises: How would you improve Jar Jar Binks?

I personally believe that Jar Jar Binks has elements of all three character archetypes above. I believe his character suffers from poor implementation of these ideas into the script. He certainly has the negative elements of a fool but is not given enough opportunity for the positive. He appears well meaning but is never anyone’s emotional center. And he is given countless opportunities to perform a heroic action but never rises to the challenge.

He, like many elements of George Lucas’ prequel trilogy, feels like a rough draft of a competent character.

So, rather than dwell on the failure – how can we fix him? Well, I for one believe that all strong character writing begins at the three scales: competency, sympathy, and productivity. A well written character has a mix of these traits on a scale system. For instance, a character can be very competent but unsympathetic or vice versa. Most writers tend to use middle degrees on these scales rather than turning one all the way up or down.

Fixing Jar Jar begins with looking at his three scales, all of which are too far down (in my opinion). Altering these scales alters Jar Jar. Writers should be careful to keep the original idea in tact. It’s easy to fix Jar Jar by transforming him into someone else entirely, but more challenging to simply make alterations.

If Jar Jar is supposed to be the fool, turn his sympathy and productivity up to have him make more emotional impact. To be an unlikely hero, turn up the competency. However you approach it, keep your archetype goal in mind.

This exercise can be a simple scene rewrite or a full plot makeover. If you’re curious to see how you did, I recommend posting on FanFiction.net. You can use a pen name and the feedback can be helpful.

Jar Jar Binks may have earned the fan’s hatred (not that it takes much) but I believe he is a character built on solid bones. Looking at his failure requires studying character construction and plot development, two things that can only make you a stronger writer. Best of luck!