Author William Faulkner once said, “In writing, you must kill all your darlings.” While some writers (like George R. R. Martin) may take this literally, I personally doubt that Mr. Faulkner meant to imply that you should send all your heroes to an early grave. No, he more likely meant that writers should not be afraid to abandon ideas, even their favorite ones.

When I write, I have many ideas that I personally love but make for bad storytelling. A lot of them involve my protagonists. Mainly, I don’t like to see my main characters get hurt. Well, a little hurt maybe – but not devastatingly crushed. While I’m sure my protagonists appreciate this – as much as any imaginary person can – it can make for a boring story.

In my last blog post, I talked about the unlikely hero character archetype. This person is always the last the reader expects to see saving the day. David defeats the giant Goliath with his wits and a well-placed stone. Well, imagine David didn’t fight a giant. What if he instead fought a middle-sized, slightly overweight man named Gerald? Suddenly the victory isn’t so fantastic.

This gets to the heart of today’s writing lesson: While you maybe shouldn’t kill all your darlings, don’t be afraid to beat them (emotionally or physically) to a bloody pulp.

Raising the stakes

Beating up your protagonist raises the stakes. David is fighting a man – not just any man, a giant – not just any giant – a warrior – not just any warrior, an undefeated warrior, someone everyone else is absolutely terrified of. At every increase of Goliath, David’s struggle seems more hopeless. However, it is making the reader that much more invested in the story. Beating an unbeaten warrior giant sounds a lot more interesting than getting the best of middle-aged Gerald.

Let me use a more personal example:

Throughout my blog you’re going to see a lot of criticism of my own writing, well let me begin with The Dreamcatchers. While I am overall pleased with my first effort, I won’t pretend it is perfect. In Dreamcatchers, the main villain is a night terror named Incubus. He’s a dangerous dude.

As a reader, you know this because he badly injures the protagonist early on, poisoning and nearly crippling him. In addition, he wins the next two encounters that he and the protagonist have. This sets up a final confrontation where it is unlikely that the protagonist (Vakarian) will win on his own.

While all this is great, part of me wished I had Incubus win more. One of the difficult aspects of The Dreamcatchers is that we never see the “real” world. Our main human character, Tony, is always asleep. Therefore it is difficult to see how Incubus is really threatening him – outside of disrupting his sleep patterns. I attempted to combat this problem by including a prologue where we see another human character suffer direct, substantial complications from a night terror attack.

Was it enough to raise the stakes? I’m not sure. I hope so. It is one of the issues I hope to address more in The Night Terrors.

Since my main human character was a child – and the book is young adult – part of me wanted to shield him from a life-and-death struggle, but this is not conducive to great writing. Look at the Harry Potter series: Aimed at (and starring) children, these books feature death, maiming, and a whole lot of broken limbs. I remember always feeling like Harry and his friends were in real danger – and that is what made their victories all the more incredible and satisfying.

To put it in simple terms: Your characters can’t get up if they don’t fall. While a stagger is less painful, it is also less interesting to read about.

Establishing a strong threat

Your protagonist isn’t the only one who benefits from a bruising plot line. One of the chief problems I see with villains today is that many of them are not very threatening. The conflict, especially in a lot of children’s entertainment, is often in stalemate – with the heroes achieving many more victories than the villains.

A huge example of this is the original Transformers cartoon. It opens with a grim situation: The war is practically over and the Autobots have all but lost. Their home planet – Cybertron – lies in the hands of the Decepticons. Megatron has more people, resources, and strategic locations. Despite this, he loses every single episode.

Suddenly Megatron doesn’t seem threatening. He’s cool – yes – but competent? He keeps a second-in-command who literally betrays him every third episode. Megatron is a victim of bad writing. He is never winning the situation because the heroes aren’t having any real challenges.

In contrast, the Megatron in Beast Wars wins every major struggle up to the end. This is made more impressive by the fact that he doesn’t have the resources of his predecessor, nor the manpower.

If you want to write a strong villain, they have to win at least 66% of the time. Not only does this make them a serious threat, it also makes it that much more satisfying when the hero prevails.

Producing a satisfying climax

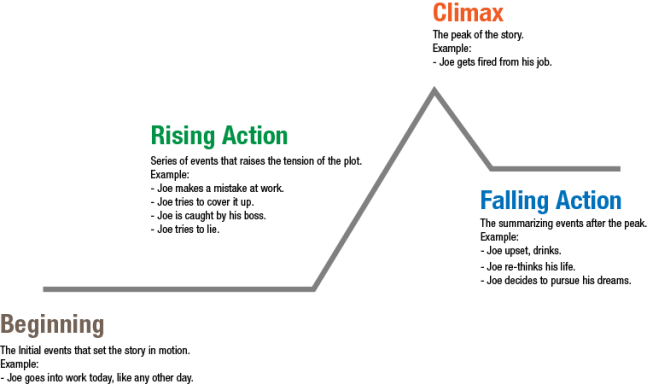

A lot of this ties into plot structure. Here is the classic plot outline:

As you can see, everything builds to the climax. The higher that point is, the more satisfying it will feel to the reader. Everything in a story is functionally in service to the climax. All of the hero’s trials and failures make that final moment – that point of either victory or defeat – all the more meaningful.

If you haven’t truly endangered your protagonist in some way then expect this moment to hit without its full impact. If you’ve written a story about a relationship for instance, but we never doubt that it will end, then the moment of salvation will come off as less of a “YES!” and more of a “Oh yeah, makes sense…”

Again, in order to pick themselves up, the protagonist must fall, albeit not always literally.