Last night, I finished watching Star Wars Rebels. The adventures of Ezra Bridger and company came to a close and, overall, I think I will look back on the series with a general thought of “It was all right, but I felt like it could have been so much more.”

The season 4 finale in particular had me scratching my head and sighing, feeling like a letdown after the superior writing of the mid-season finale. The sad part is, after the season 3 finale, I wasn’t surprised.

Star Wars Rebels hopes to teach its audience many lessons about life, morality, and consequences. However, I think it best serves as a message to writers and, unfortunately, I believe it will go down as a cautionary tale more than anything else. Let’s focus on the writing of Rebels and break down exactly what I’m talking about (warning: spoilers to follow).

The Importance of Payoff

When I think of Rebels, I label it as a show that raises many good questions and ideas. Ezra is a jedi trainee outside of the temple – at a time when temptations to the dark side should be at their peak. After all, he’s relatively powerless against overwhelming odds, and his chief drive is to protect his new family. On top of that, he’s a young kid in the middle of a war. Sound familiar?

And the show seems to be aware of this. We see Ezra tempted by the dark side. In pervades all of season 2 and is the dominant theme. Kanan is worried, stormtroopers are mind tricked into murder/suicide – it seems like Ezra’s “soul” is in real danger.

Then he meets Maul and Kanan gets blinded and…that’s it? The temptation of the dark side effectively vanishes for the remainder of the show, despite having numerous opportunities to resurface. This makes Ezra look incredibly strong-willed, which is odd because he doesn’t seem to really mature much elsewhere. He is still impetuous, he’ll still do anything for his friends, he still is placed in many life-and-death situations.

But the payoff never comes. Star Wars Rebels does this with an art form – build to events that never happen. Let’s go through the seasons. Season 1: Pretty solid – actually not much to report there. Season 2: The temptation of the dark side – payoff: Kanan gets blinded by Maul and Ezra is forever “cured.” Season 3: The rebels face Thrawn, who continually lets them go – referencing a larger plan – Payoff: Thrawn stumbles onto their base through unrelated events. Season 4: Lothal is revealed to be deeply connected to the Force, including force wolves and a portal that controls time – payoff: Ezra calls in some space worms from season 2 to save the day…?

Yeah it’s not great. Throughout its four season span, Rebels continually raises plot lines that it doesn’t pursue to conclusion. It isn’t the first show to do this, nor will it be the last. Thematically, it is more challenging to explore a theme in its entirety – but also much more rewarding. In Avatar: The Last Airbender, the audience gets the feeling that the two writers really thought about war, violence, and resolving conflict. Almost every aspect is thoroughly explored, and I never once got the impression the writers were talking down to me.

If Star Wars Rebels can teach you anything about writing, it should be that plot threads should be fully developed ahead of time (or refined in editing) to erase most of the dangling story points.

Creating Characters with Arcs

All through season 4, there was one character I was wondering about: Zeb Orrelios. Namely, the thought on my mind was “What happened to him?” Zeb has no character-focused episodes in the final season, instead sitting on the sidelines. I also started thinking about his character. Throughout the series, he did have several arcs – he found his people, persuaded Agent Kallus to rebel against the Empire (really easily), and…that’s it.

And while Zeb had his character arcs – I couldn’t really figure out what he ever did for the main plot. He was always there, it’s true, but his stuff felt very superfluous. Kallus’ betrayal never amounts to much (he’s in season 4 even less than Zeb). In the greater struggles of Rebels, Zeb is a passive character, largely just along for the ride. He could have left at any point without making a noticeable impact. There is no “it” that he has that the other characters don’t.

And I feel like this is true of a lot of the main characters in Rebels. Their arcs are general or barely there. How does Sabine Wren really change from the first to the last episode? How does Hera? Most characters are very static – with only small deviations (hey remember that time Sabine left the rebels for all of three episodes?).

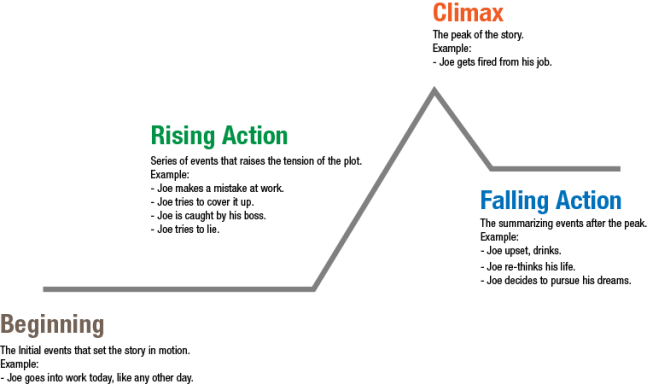

Even Ezra – the main character – does the bulk of his changing in the first season, going from a loner to a team player. He doesn’t really sway much past that point. Many character arcs relate to the goals of the story. Here is a chart:

Most of the characters never go through this change, in part because many don’t have serious flaws to be corrected. In much the vein of traditional Star Wars archetypes – the good guys are good and the bad guys are bad (in every sense of the word). It fits but…eh, it’s a bit dull for a series.

The Importance of an Intimidating Villain

I’ve already written about this in an earlier post on Thrawn, as well as touched upon the broader writing lessons in my ‘Beat Up Your Heroes‘ post – but it bears repeating here. The villains of Rebels were typically dull and uninteresting. Part of this was the movie armor. Darth Vader is imposing as heck but then…stops pursuing them? The rationale is never given.

Likewise, it is a joke by this point that stormtroopers can’t aim, but Rebels elevates this to laughable heights. The final episode features stormtroopers firing – and missing – a stationary target roughly five feet in front of them. It would be okay if I didn’t think the show wasn’t trying to be serious – but you can’t have serious when your standard villains are less threatening than unarmed children.

The rebels are never beat up – for an oppressed group, they seem to be doing very well for themselves. Only one of them dies, and even then it feels more like the will of The Force than the actions of the villains.

If you want the hero’s victory to feel incredible, they’ve got to earn it. Rebels ends with a James Cameron’s Avatar moment: The intergalactic threat is defeated and just…leaves? Never comes back? What? It’s a happy ending but it doesn’t feel like an earned ending. With everything at stake on Lothal – why would the Emperor, a dude so evil he looks like Satan, let Lothal go?

Also if that’s all it took to free Lothal then they could have done it seasons ago – just saying.

Managing Escalation

At its heart, I think the Rebels‘ writing team had a real problem managing the escalation of stakes. When it was a little show about a small group of rebels on one backwater planet, resisting whatever the Empire had time to throw at them, it was believable and fun.

Toward the end, they were blowing up star destroyers left and right and crippling whole operations like it was nothing. How did these guys not single-handedly defeat the Empire?

There is one episode in season 4 where they fight 2 trandoshan slavers (one voiced by Seth Green doing his Cobra Commander voice) and they struggle. I mean, it takes them a whole episode to capture the freighter. While I liked this hearkening back to the first season’s scale, it stuck out to me. Why were they having so much trouble with 2 non-military personnel? After all I’d seen them do?

I could go on – and I’ll probably reference Rebels again in future articles. For now I will just say this: A lot of good stories can be ruined by laziness or sloppiness. I don’t think Rebels was ruined, but it was never great. If it wasn’t Star Wars, I don’t think people would have been as hooked.

When writing your stories, manage your payoffs – keep character arcs in mind – and write to suit escalation.