The release of Dragon Age: Inquisition is upon us. Bioware‘s third in its series of medieval fantasy role-playing games looks impressive, and has already amassed a slew of favorable reviews before its release. This is the first Dragon Age game since 2011. It is odd in this day to find such a high-budget video game release being given so long a development schedule. To put it simply: four Call of Duty games have been released in that time. Of course, the counter argument could be that EA lets Bioware take longer to develop their games but… that is not true. Mass Effect 3 was released just over two years after the initial release of Mass Effect 2 (not including the dlc release dates), and that title was delayed. Dragon Age: Inquisition‘s long development time might have a lot more to do with the reaction to its predecessor, 2011’s Dragon Age II.

Dragon Age II received positive reaction from critics, but to look at the game’s user feedback is a different story. Many fans of the series condemned the sequel, calling it a rushed, cheap cash-in attempt on the first game. While not all the response was that critical, it came as a personal surprise to me. I am a big fan of Bioware, I love their games and quite enjoyed playing through Dragon Age II when it was released. That said, the game undeniably has weaknesses. While video game taste will always be a matter of perception and personal taste, there are a few areas where it is very possible to be objective. Let us examine the definite negatives and positives of Bioware’s most controversial release.

Level Variety

This is the first and largest negative aspect of Dragon Age II. The first game, Dragon Age: Origins, was known for its sprawling world and massive amount of dungeons. Last night, my friends and I tried to remember all the different dungeons in Dragon Age II. We concluded that their were basically six… in a game that took at least twenty hours to beat. The number is not the problem, if each dungeon was vast and took a lot of time and felt unique, that would be one thing. Dragon Age II recycles the same six small dungeons over and over again for its quests. The player better enjoy each dungeon’s design, because they will be seeing them a lot. True, there are a few others that are called in for special occasions but really it is difficult to overlook the impression this leaves. Reused dungeon design gives the definite feeling of a rushed game and chips away at the feeling of immersion. “Let’s go into this alley? Oh, you mean the alley that looks identical to every other alley in the city? Sure… why not.”

Glitches

Glitches can make or break any game. The best video game’s can be tarnished and company’s reputations ruined over releasing products full of bugs. Unfortunately, Dragon Age II is such a game. Having completed multiple play-throughs, I personally encountered multiple glitches both times. These were not simply graphical errors either, where the models and textures go wonky. On several occasions, the game encountered errors which prevented quests from being completed or even attempted. In a game where going on quests is essential (the main drive of the entire video game), this is unacceptable. What made it worse was that Bioware and EA put out several expansions of paid dlc… without ever fixing the bugs in the main game. Don’t worry, the downloadable content contains errors too. It is a tough sell to continue to support a game that its own maker can’t even be bothered to fix.

These are the only two clear failings of the game but – they are large failings. Whether a player liked the story is subjective. Whether a player liked the companions is subjective. Not being able to complete quests due to poor design – that is a very objective complaint. But anyway, about those companions…

The Companion Archs

Not to say that Dragon Age: Origins had poor companions, it did not. That said, certain mechanics of the system felt tacked on and were easy to manipulate. Companion loyalty simply came down to gift giving, it served to undermine the organic nature of forming a party. This was thankfully no longer true in Dragon Age II. While still not perfect, the companion system felt more natural this time around. Everything came down to how the player protagonist interacted with the companions. Gifts still played a role but it was reduced. The resulting effects caused the player to more carefully consider their options, especially given that companions could turn to enemies given the right circumstances.

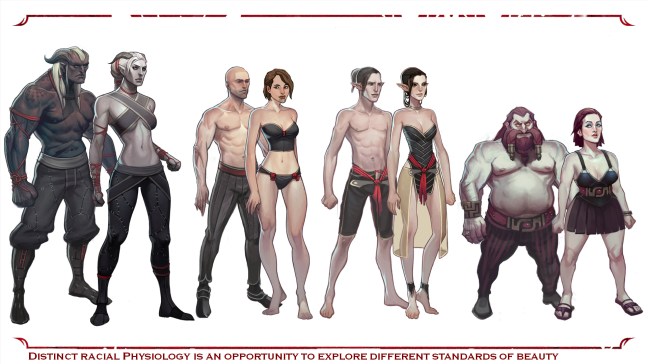

The Art Style

Like it or not, there is no denying how much more creative the art style appeared in Dragon Age II. Each race became more distinctive looking. Quanari, for instance, became much more easily identifiable. While Origins was not weak on design, Dragon Age II did a lot to improve it. The game is definitely stylish.

Ultimately, Dragon Age II is bizarre in the fact that it is exceptional in both respects. What works in the game works very well and what does not fails miserably. There was no middle of the road in Bioware’s second fantasy epic. At the end of the day, however, this game might be one of the finest mixed bags ever made. It is certainly one of the few I can honestly say I would recommend to people looking for high quality… just watch out for the low.